Cardiac Amyloidosis Needs to Be on the Decision Tree

Cardiac Amyloidosis Needs to Be on the Decision Tree

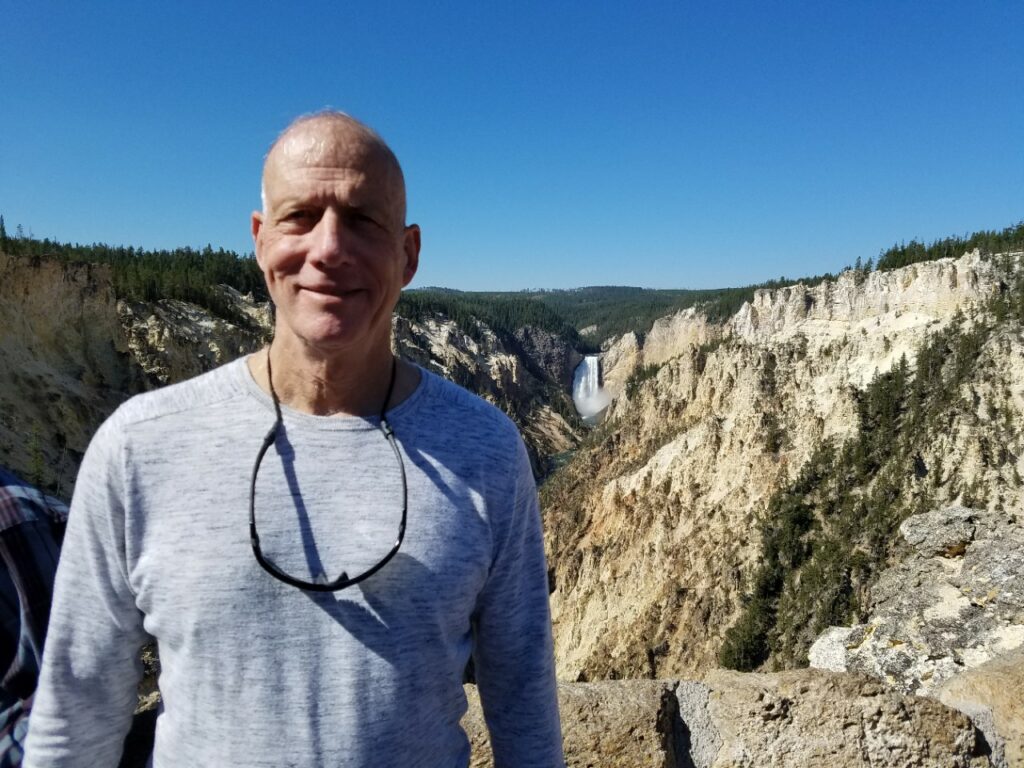

Gary Supnick

Retired Marine Corps Colonel & Heart Patient

For U.S. Marine Corps Colonel Gary Supnick (retired), the path to being diagnosed with transthyretin (TTR) cardiac amyloidosis was far from straight. Over a period of nearly five years, starting when his primary care doctor heard something “not quite right,” Col. Supnick underwent more tests than he can recall only to be told that the cause of his enlarged left ventricle was idiopathic.

was idiopathic.

Then came cardiologist Eric Harrison, MD, who saw something on Col. Supnick’s MRI and had a eureka moment. “Dr. Harrison told me, we need to check you for amyloidosis,” Col. Supnick recalls.

The initial tests for amyloidosis came back negative, and Col. Supnick had his doubts. “All that was left was a heart biopsy, and I was close to refusing to do it,” he says. “But we went ahead and, sure enough, the biopsy came back positive for wild-type TTR amyloidosis.”

Once he had the diagnosis, everything changed for Col. Supnick. In short order, he was at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., gaining insight into things that hadn’t made sense in the past. For starters, why his workouts had gotten so much harder in the previous decade, so much so that he, a 30-year infantry officer accustomed to doing marathons, had found himself opting for a bike ride over a run.

“I’d attributed the decline in physical performance to aging, but now I think it was the early signs of my cardiac amyloidosis,” says Col. Supnick. His Mayo Clinic cardiologist, Martha Grogan, MD, told him that his overall physical fitness and lean body mass had helped mask the symptoms. “She showed me my tests compared to those of a typical 60-year-old man, and said, ‘Make no mistake, this is a very sick heart,’” Col. Supnick remembers. “She’s been spot on about everything from day one.”

Dr. Grogan helped him modify his workouts to avoid extra exertion on his heart, had him adjust his diet to low-sodium and limited fluid intake, and got him into a tafamadis clinical trial. “Until they come up with a way to pull the amyloid crap out of my heart, my plan is staying active, staying lean and tafamadis,” he says. It’s working so far. “I’m still active. I can’t sprint or run 5Ks like I used to, but my wife and I hiked Diamondhead in Hawaii this year. Last year, we went to Yosemite and the Grand Tetons, where the air is thinner. I had to take breaks, but I made it.”

Besides following his doctors’ recommendations to the letter, Col. Supnick is committed to learning everything he can about cardiac amyloidosis. When Dr. Harrison mentioned that ASNC was hosting a cardiac amyloidosis workshop in Florida last March, Col. Supnick attended. Calling on the concepts he learned as a health/physical education major, he wasn’t daunted by a course designed for physicians. “It never hurts to get smarter on aspects of your condition and what’s being done about it,” he says. Among the new things he learned is that there’s a noninvasive imaging option, Tc-99m-PYP, that makes it possible for some patients to be accurately diagnosed without undergoing a cardiac biopsy.

For Col. Supnick, the most important message from ASNC’s workshop—and the one he wants more medical professionals to learn—is that doctors need to get cardiac amyloidosis on their radar and into their diagnostic algorithms. “They’ve found it’s a bigger, more widespread problem than they thought,” he says. “So, once a doctor has ruled out other signs and symptoms, they should automatically check for amyloidosis. It should be on the decision tree. It shouldn’t be a eureka moment.”

ASNC agrees and has expanded its cardiac amyloidosis workshop series to include the following 2020 programs:

- Saturday, March 21, in Hollywood, Florida. The Cleveland Clinic’s David Wolinsky, MD, MASNC, will host a half-day program titled, “Wake up and Look Around: Towards Early Recognition, Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiac Amyloidosis.”

- Saturday, April 4, in Houston, Texas. Houston Methodist Hospital’s Mouaz Al-Mallah, MD, MSc, FASNC, will direct “Cardiac Amyloidosis: From Missed and Undiagnosed to Common and Treatable.”

- Friday, April 17, in McLean, Virginia (just outside of Washington, D.C.): James Udelson, MD, MASNC, of Tufts Medical Center, and Prem Soman, MD, PhD, MASNC, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, will chair “Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Practical Primer.”

ASNC invites all clinicians who are interested in learning when to suspect cardiac amyloidosis, how to arrive at accurate diagnoses, and disease management strategies. LEARN MORE.